I first learned the word kabsat from my paternal grandmother, Mama Ching. She held a newborn baby swaddled in a cotton receiving blanket. Mama took the baby from her and handed it to me. “Happy Birthday!” I had just turned five.

The previous year, I visited my aunt, who gave birth to a boy. Mama Ching took me to Manila for a visit. When it was time to go home, I threw a tantrum because she would not let me bring the baby home. I kicked, screamed, whimpered, and cried for the five-hour-long bus ride back home. She tried to quiet me, “Naccong, you have to pray to the Lord, and ask your Mama and Papa.”

My prayer was answered exactly a year later. We nicknamed him Pepot, little Pepe after my father. The tiny creature fascinated me. Mama cradled him in her arms, and I peered closer. I heard him suckle desperately.

“Mama, what is he doing?”

“He’s drinking Mama’s milk.”

“I want to taste it too!”

“Pshh,” she dismissed me. I was serious and brought a tablespoon from the kitchen. I stood there until she relented and filled it.

“Mm, tastes like am,” I said. Am is the rice water that Mama Ching gave us when we didn’t have milk in the house. She cooked rice with extra water, and when it boiled, she took out a cup of the milky fluid and flavored it with sugar for our snack.

“Did I drink your milk too?”

“No, I had to return to the university,” where she was a professor. My face fell, and she lifted my chin. “Your nurse fed you Enfamil. It was the best brand!”

Mama Ching stayed with us in the baby’s early days. She cooked pansit, lumpia, and cascaron, mounds of rice flour deep-fried in brown sugar. She gave us candy, despite Papa’s prohibitions. She changed the cloth diapers, twisting a long rectangular strip in the middle and securing them with large safety pins on the sides. I was alarmed at the stump on Pepot’s navel. It was about an inch long, crusty, and a little stinky.

“Does it hurt?” I asked.

“Oh, no,” she assured me. It just falls off, like yours did.

“I had one too?” my eyes widened like saucers.

“Yes, all of you. That’s why agkakabsatkayo.” You are all siblings.

She added, “You were all connected to your mother. Kabsat means brother or sister. It’s short for kapugsat.” Snapped from the same link.

“Like longanisa?” I imagine the sausages marinated in vinegar, salt, and garlic. Mama Ching always brought them from Vigan when she visited us in Baguio.

She roared with laughter, rocking her head backward. “Nalaingka la unay.” You’re a little smart one.

“Did you know that another name for kabsat is kabagis?” Mama Ching liked to teach us Ilocano words, fearing we would forget her mother tongue.

Now I was confused. Bagis meant intestines. How can I have the same intestines as my brothers and sisters? Years later, I checked the overlapping plates of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and there was no way people could share intestines unless they were conjoined twins.

Growing up and to this day, I do not have a massive group of friends. Aside from a few best friends and a close group, I had never been the social butterfly in the family. I preferred to sit in a corner, reading. Or perhaps it’s because I had built-in friends. I had an older brother, two older sisters, thirty-nine cousins on Mama’s side, and fourteen on my dad’s. That’s counting only the first cousins.

On a summer vacation in Ilocos, I referred to a relative as “kasinsin,” which I thought meant cousin. An aunt corrected me, “He’s not your kasinsin, he’s your kapidua.”

“Ha?”

She counted for me, “Maysa, dua, tallo.” One, two, three. The relative degrees follow the same order—kasinsin, kapidua, and kapitlo for first, second, and third cousins.

“Then what’s kabagian and kailian?” I heard this a lot when they introduced me to the townsfolk.

My aunt laughed at my rudimentary Ilocano. “Kabagian comes from bagi - same body. It means relatives. Kailian comes from ili - town.”

In Ilocos, towns were small and it was hard to distinguish between relatives and mere townmates. Thank goodness Mama was the master of family trees. I wrote about it in my earlier post.

Are Ilocanos clannish?

A WordPress blogger iamcalledDENCIONG addressed this question in 2012:

It has been said that Ilocanos are the most clannish ethnic group in the country. This clannishness was born out of the difficulty of life and has produced Ilocano communities elsewhere in the land.

Wherever they went, the Ilocanos have brought with them this clannishness that has made them endure and which has created that amorphous reality called the “Ilocano Nation.” The Ilocano is different from other ethnic groups of the Philippines, not because of the anthropological or epidermal characteristics, but because he is the creation of geography, culture, and history. The land of the Ilocanos could not been peopled or developed by a less noble breed. It is the clannishness that makes for the Ilokano family solidarity.

I am not sure about the amorphous Ilocano Nation. Certainly, the Solid North of the Marcos era had liquefied enough to allow People Power to happen in 1986.

My Uncle Padi, a priest in the Diocese of Nueva Segovia, strongly advocates for the townspeople and their natural environment, in addition to his regular duties. He challenges the misconception that Ilocanos can be classified as a single entity blindly following one leader. He often advises his parishioners to vote with their conscience. “We may be Ilocano, but we are not naive.”

I suppose being clannish resulted from the necessity of pooling resources to survive harsh conditions or fight neighboring threats. My chemistry teacher used to say, “Blood is more viscous than water.”

I have a large, extended Ilocano family, and I can see how tight it can be. The upside is that we can rely on them for help or support.

I don’t see this as an exclusive Ilocano trait. Families from other provinces do the same. They also pull together through thick and thin.

I am sure of this—siblings have a unique unbreakable bond.

My siblings and I cemented our bonds and often considered ourselves like the operators of the Japanese anime robot from the 1970s - Voltes V. We used the catchphrase, “Let’s volt in!” long after Marcos banned the show for being “too violent.”

We may have disagreements like any other family, but our default modus operandi is like the plot to Voltes V. We cannot surmount our struggles alone, but together, we can subdue the fiercest enemy. My maternal grandmother, Lola Andang, reinforced this idea. “When you grow up, your parents will die. Your spouse may leave, but you will always have your brothers and sisters.”

Pepot and I immigrated to the United States in the late 1980s, as the only children in the family petition. The older ones aged out, disqualified when they turned twenty-one. Pepot returned to the Philippines during his teens, after some struggles in the US. He reversed his fortune by finishing college, meeting the love of his life, and having three daughters.

It was lonely being an only child on this side of the Pacific. Mama petitioned for my siblings, who followed decades later. Imagine my joy as each of them immigrated. The five of us reunited in 2021, a quarter century later, when Pepot returned for good. Mama’s children were complete, as was my happiness.

Discussion:

After I posted this, my mom commented on Facebook:

Ilocano dialect does not have the letter “k”. Correct llocano spelling is with a “c”. Cabsat not kabsat.

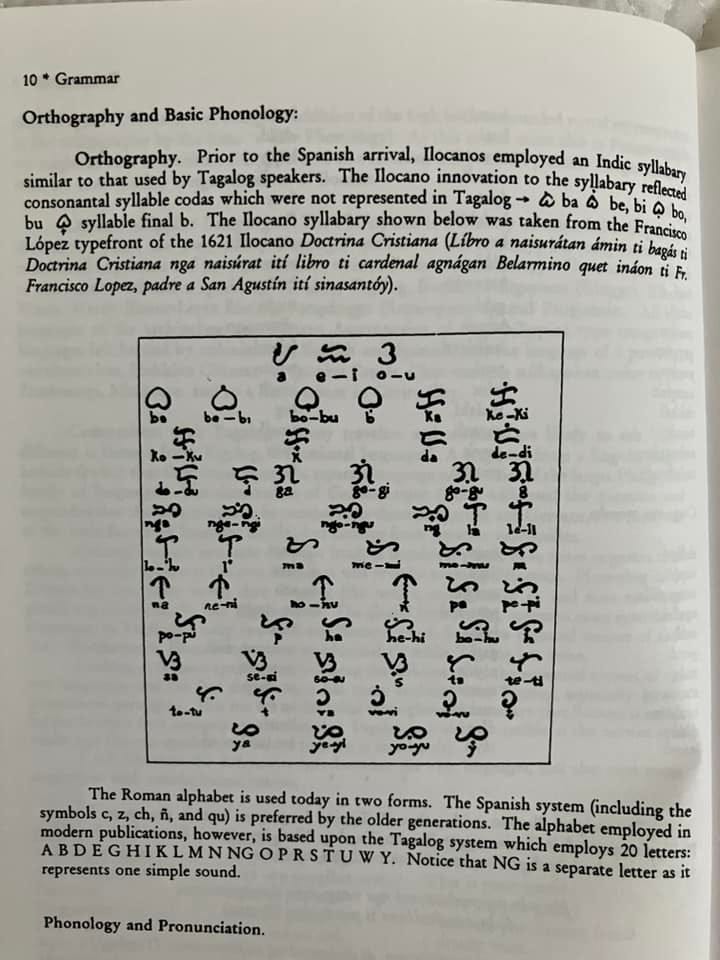

So I consulted with my Ilocano linguistic expert at the University of Hawaii in Manoa, Dr. Aurelio Agcaoili. He said the letter k was used in precolonial times and is considered original or high Ilokano.

A few dictionaries supported his claim. Carl Galvez Rubiono described in the Ilocano Dictionary and Phrasebook how spelling with c and k is a generational preference. That makes sense. My grandparents always wrote naccong (my child), but it could also be spelled nakkong. My mom’s parents were born in 1898 and 1902 and adopted the Spanish spelling style, which is how they would have taught my mother.

Recommended Reading:

Kamakailan ko nalang din nalaman na parehas lang pala ang kabsat at kabagis. Naalala ko noon may mga tiya akong Ilocano, at nababanggit nila ang salitang kabagis at pangalan ko at ng aking mga kapatid. Ang akala ko noon sinasabi nila na kabagis=kamukha kaya naman todo kong tinatanggi na hindi ko kamuka ang aking mga kapatid (oo hindi ko sila kasing-cute). Ahahah