E is for Eleccion, Empleo, and Emperial - How we got our last names from the Catalogo Alfabetico de Apellidos

ABCs of Recovering Ilocano Series (#5 of 26)

It is 1849 in the Philippines, under Spanish rule. Imagine that you are the head of your family and are presented with a list of last names. Your hometown was assigned a letter from the Catalogo Alfabetico de Apellidos. Before the municipal governor and cabeza de barangay, you will declare a name for your descendants. What would you choose?

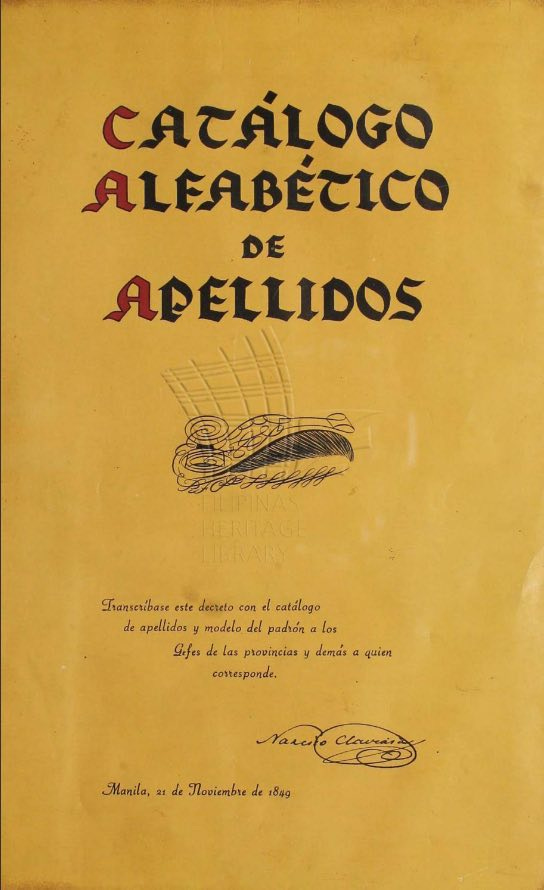

Check the Catalogo Alphabetico de Apellido if your family name is listed :

Ayala Museum Library copy of the Catalogo, Filipinas Heritage Library

I first heard of the Catalogo from my mom, who since childhood loved tracing her family history. This decree by Spanish Governor Narciso Claveria was also known as the alphabetization decree. Previously, names were adopted from nature, Catholic saints, geographical locations, and other descriptive qualities. They were not passed on in Western fashion from father to son. In short, this wreaked havoc on the Spanish government for assessing taxes, tracking migration, and establishing paternity or inheritance.

Mama’s forebears picked Eleccion, Empleo, and Emperial (later Imperial, the letter I is missing in the copy in the link above). Her relatives took Ea, Ebojo, Edralin, Espejo, and Europa. Looking at her family tree, it was easy to see who was native to the town because their last name started with an E. Mama called the foreigners “dayo,” those who settled there for business or married a native-born San Estebanian. An example would be my father, whose last name Ragasa indicates that he was born in Santa Catalina, Ilocos Sur. My address book is half-filled with R names such as Rafanan, Rapacon, Rabe, Rapanut, Ragunton, and Reyes.

We also had relatives whose names did not end with E such as Abad, Benitez, and Vergara, as the Catalogo made an exception for those who could prove its use for more than four generations.

I reflect on the wisdom of my forebears, and cast my interpretation of their choices from the Catalogo:

Eleccion - I elect to adopt attitudes that promote my identity as a proud Filipino and Ilocano.

Empleo - I am hardworking.

Emperial (Imperial) - I can be the king or queen of my identity.

Ragasa - I am intrepid. As a verb, rumaragasa means rushing, as when a small creek turns into a torrential river during the stormy season.

Benitez - I am blessed.

Mama’s father, my Lolo Abdon, was a Vergara. I often heard that his patrician nose, high forehead, superior intellect, and fair skin came from the Spanish. He could trace his lineage fourteen generations back, to Padre Agaton Vergara, a Spaniard from Bergara, a town in the Basque Region of Spain.

Wait, Padre, as in friar?

Yes, a prayle. Anyone who has read the required texts in high school, Noli me Tangere and El Filibusterismo by Jose Rizal can infer the story of clerical abuse and absolute authority over the indios, the native population. I cringed to think that somewhere in our distant past lurked a Padre Damaso or Padre Salvi, corrupt friars who fathered children and passed on their Castillan genes. Later, generations proudly claimed to be mestizos or mestizas, children of mixed heritage.

One look at me and you can tell I’m not a mestiza. Ancestry DNA can prove it too. Mama suggests that I must have inherited my features from the Chinese. “They traded with the Philippines even before the Spanish came.”

But I digress. What should I do with the information about Padre Agaton Vergara?

Lately, I have been reflecting on the meaning of the word decolonize.

Merriam-Webster defines it as:

1: to free (a people or area) from colonial status : to relinquish control of (a subjugated people or area)

2: to free from the dominating influence of a colonizing power especially : to identify, challenge, and revise or replace assumptions, ideas, values, and practices that reflect a colonizer's dominating influence and especially a Eurocentric dominating influence

Many have heard the saying about the Philippines’ colonizers—three hundred years in a convent and fifty years of Hollywood. In Wisdom and Silence, Danilo Alterado from Saint Louis University, my alma mater in Baguio City, adds two more colonizers: the Japanese during World War II and the imposition of Tagalog as the national language. He proposes that losing fluency in native languages such as Ilocano or Cebuano became an internal form of colonization.

This situation is not unique to the Philippines. A book review of Decolonising the Mind by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o shows the impact of colonization on African literature:

Language as Cultural Domination

Thiong’o shows us how forgetting one’s language means forgetting one’s culture, community and sense of being.

I recently spoke on Decolonizing My Flat Filipino Nose (see entry on May 28, 2024). I noted that our relationship with our colonial past is complicated. Decolonizing does not easily translate to changing our country’s name to remove Philip IV of Spain’s legacy, although that has been proposed. We need not divest our last names, reshape our noses, or convert to another faith. It would be like stripping ourselves of our culture and our identities.

The one thing we could change is our attitude. Maybe in doing so, we can reclaim the pride of our pre-colonial ancestors.

Read Webster’s second definition of decolonization above.

Let’s try this formula for freeing ourselves from the dominating influence of a colonizing power:

Identify an assumption, idea, value, or practice.

Flat noses are ugly. Sharp noses are beautiful.

Challenge an assumption, idea, value, or practice.

Are flat noses ugly? Says who? Noses are made for breathing and smelling. Can you do these bodily functions? Try an app to switch out your nose to a different one. Does it even look like you?

Revise an assumption, idea, value, or practice

If you don’t like your nose and can afford rhinoplasty, do it if it will save your sanity or make you happy.

If you don’t like your nose because of other people’s opinions, work on your self-esteem. Plastic surgery won’t help.

If you can breathe and smell, be proud of your nose. You are unique and you are beautiful.

Replace an assumption, idea, value, or practice.

Flat noses, sharp noses, and everything in between are beautiful. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and if you look at yourself with love, nothing else matters.

What does your last name mean? Does it reflect your culture? How can you decolonize the mind?

Recommended Reading:

Decolonizing the Mind by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Jen Soriano: Letter To My Four-Year-Old Son: An Epistolary Book Review

Rizal Law: Why every student after 1956 had to read Noli me Tangere and El Filibusterismo

Hi Rachielle! My late father's father had roots in Santa, Ilocos Sur - his mother was a Benitez and his father was a de Peralta. Also, interesting trivia about the Vergaras! I came across a website written in the 90s by a Filipino who migrated to Australia and tried to trace the entire clan. There are Vergaras in Pampanga (where my line of Vergaras came from), Nueva Ecija, Bulacan, the Ilocos region, and I think even in the Visayas.

Ay nako! Our family name Cariaga is on page 28! Interesting looking at the original 1849 edition. "You children must be informed of their family name....etc"