R is for Ragsak (Happiness)

Translating my Father (#18 of 26 in the ABCs of Recovering Ilocano)

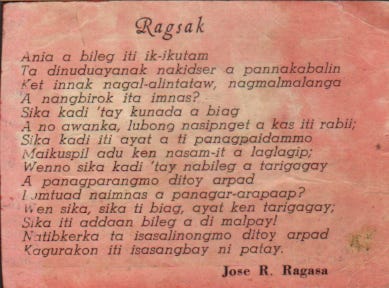

In our family, I have become the designated keeper of memories. So it was no surprise when I received a letter from my sister enclosing a poem my father had written long ago. By the clipping’s appearance, I estimated it to be written in the mid-1960s. Mama had put it in a magnetic album, the sticky type that makes scrapbookers faint with its acid content. My sister rescued it before it crumbled into oblivion.

There was no indication of where it was published, but I had two guesses: White & Blue, the Saint Louis University student paper, or Bannawag, the Ilocano magazine.

My parents met at Saint Louis University in Baguio City, a four to five-hour bus drive south of their hometowns in Ilocos Sur. Papa first saw Mama during Varsity Night and told a friend, “I will marry that girl, by hook or by crook.”

Regional associations such as the Ilocos Sur Varsitatians helped students ease their loneliness away from home. They organized dances and socials, a break from their studies and dormitory life routine. Papa was the president of the organization, and Mama was the secretary. He was taking up Political Science at SLU, a likely choice as his father was the Mayor of Santa Catalina. He found out that Mama was studying Accounting, so he used the pickup line, “Would you help me with my math assignment?”

He wooed her with poems, declaring his love in Ilocano poems that mirrored the effusive poetry of the daniw. I wrote about it in D is for Daniw and Dung-aw in this series.

Erratum:

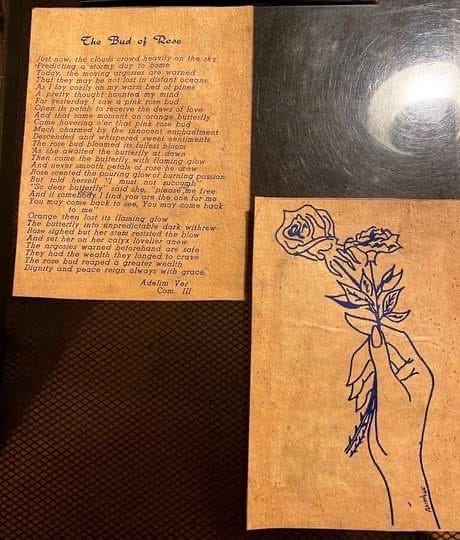

All my life, I believed Papa submitted to White & Blue under the pen name Adelim Ver, a portmanteau of Mama’s name, Adela Imelda Vergara. When I published this article, Mama texted me, “I am Adelim Ver! Your Papa never wrote in English, only in Ilocano!”

It is possible that Ragsak was published in Bannawag, for which Papa wrote short stories starting in his early twenties. Papa had loved this magazine in his youth, often stealing his grandfather’s stash and reading them under the stairs of the big ancestral house in Subec, Santa Catalina. He had an accomplice, his younger cousin Maria, whom I called Auntie Mining.

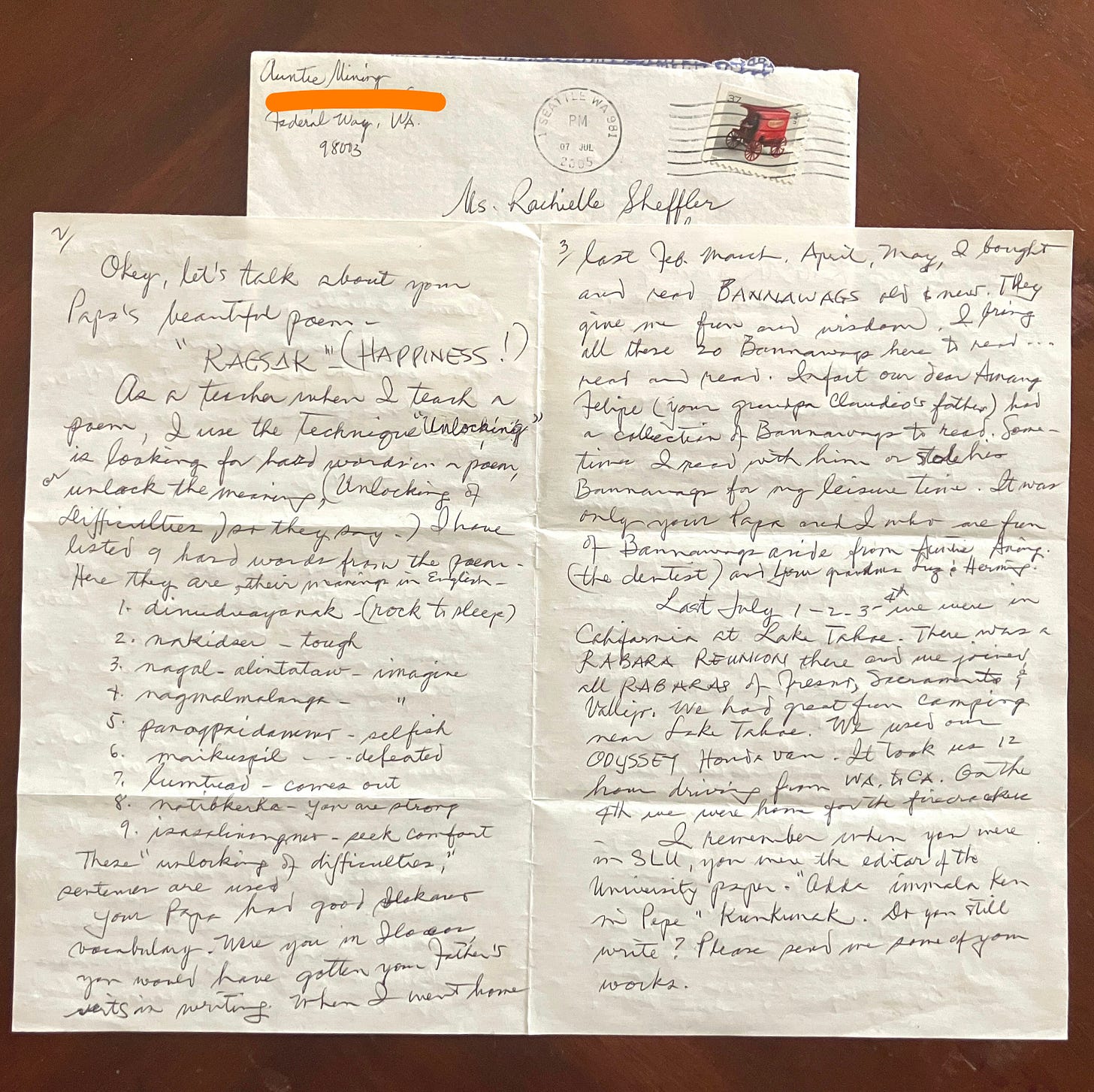

I sent a copy of Ragsak to Auntie Mining for a translation. She and I corresponded in long letters, as she had never taken to the internet. She often expressed regret that Papa passed away before she immigrated. “I had always dreamt of him standing at the airport, and he would have said with a big smile, ‘Welcome to the USA.’ ”

Auntie Mining was Papa’s biggest fan, and when I started writing for the White & Blue in college, she also became mine. It warmed my heart when she thought I had the potential to inherit Papa’s talent.

“Adda immala ken ni Pepe.”

Your Papa had a good Ilokano vocabulary. Were you in Ilocos, you would have gotten your Papa’s merits in writing.”

Do you still write? Please send me some of your works.

She described how she taught poems in school, using a technique called “unlocking the difficulties.”

Look for the hard words and unlock their meanings.

There was only one problem. Papa wrote in nauneg nga Ilocano, a literary language more appropriate for publications like Bannawag, and not used in casual conversation.

I grew up in Baguio City, where we spoke a dialect mixed with indigenous expressions such as “Anya ngay?” (How are you?). In the summers when we visited Ilocos, our speech amused our relatives. They called it “Ilocano nga Igorot.”

In Ilocos, nauneg nga Ilocano gave justice to the emotions and poetry in stage dramas called Zarzuelas. Papa was well-versed in its delivery during those plays. He often played the lead actor, because he could sing, dance, and play the violin. Auntie Mining or another cousin would perform the lead female role.

Auntie Mining picked nine words to unlock from Ragsak, but everything was difficult for me, and I put the letter away. When I took a deeper interest in Papa’s writing, Auntie Mining had also passed on.

I was listening to a QWERTY Podcast when a line struck me. The host, Marion Roach Smith, interviewed an author about her book, Read Until You Understand. The title came from an inscription Farah Jasmine Griffin discovered on a book her father had given her. She was nine years old when he died, and she described life afterward.

“I chased my father in the ideas he bequeathed me.”

That was it—what I’ve been doing all along. Papa died in 1993 when I was twenty-five. Another twenty-five passed before I began a quest to inquire into my father’s mind. I obtained Ilocano dictionaries. I consulted with family, and some of them shook their heads at the complexity of the language. A friend who grew up in Bicol (Camarines Sur) suggested a trick he used when he was stationed as a lay minister in Ilocos.

“Read the Ilocano Bible. You already know what it means in English.”

To my surprise, it worked. During the pandemic, I tuned in to my Uncle Padi streaming Sunday Mass from his parish in Magsingal, Ilocos Sur. Since I was already familiar with the Catholic rite, learning Ilocano in context made it easier to grasp the message.

I think of Auntie Mining often. This letter about Ragsak like many others, connected me to my father in ways I would never conjure on my own. In refusing to translate the poem, Auntie Mining gave me a gift. Unlocking difficulties is not only for poems.

I realize in many difficult situations, I have to find my way. It is a rocky path, and I cannot leave any stone unturned.

Ragsak by Jose Rosario Ragasa

Happiness (A Rough Translation) by Rachielle Ragasa Sheffler

What power do you possess

That lulls me into a strong sense of what can be?

So I wonder, and lost in thought,

I search for the sweetness of paradise.

Are you the one they say is life

That in your absence, the world is dark as night;

Are you the love when ripped from my arms

A million memories dash to the ground;

Or are you the force of desire

Whose appearance by my side

Fulfills my sweetest dream?

Yes, you, you are the life, the love, and my most fervent wish;

Your strength comforts me like a sheltering tree!

I would then detest the encroachment of death.

And here it is - Mama’s proof that she was Adelim Ver (Com III means she was a third-year student in the College of Commerce at SLU)

Ilocano Resources:

Ilocano Dictionary and Grammar: Ilocano-English, English-Ilocano (PALI Language Texts, 17) by Carl R. Galvez Rubino, University of Hawaii Press, 2001

Ilokano Dictionary by Ernesto Constantino, University of Hawaii Press, 1971

Naimbag A Damag Biblia: Ilokano Popular Version / Black Ilokano Hardcover Bible with Thumb Index / Modern Translation / 1996 Print Iloko Edition by Philippines Bible Society, 1972

Oh, this was so precious to read, Rachielle. Thank you for sharing a piece of your family's history with the world!

So, so lovely. It's so interesting how many languages around the world have this distinction between the literary language and what is spoken.