In the Ilocano language, Manong means older brother. I have only recently learned of a different meaning and the significance of the term in Filipino immigration history.

In 2020, my family planned a reunion to commemorate our matriarch's hundredth birthday anniversary. Mama Ching, my paternal grandmother, died in 2002. Although her memory is still fresh in my generation, the next generation of her great-grandchildren have only heard of the legend.

Covid canceled the event, and we figured out this thing called Zoom. Uncle Padi streamed Mass from the Philippines, and we shared stories afterward. At the end of the meeting, my oldest aunt said, “Give all your stories to Rachielle and she will write a book.”

It wasn’t the first time that I was tasked with doing this. When my grandmother started to decline around 2000, an aunt wanted to capture Mama Ching’s storied life, from a small girl in Bacsil, Lapog, Ilocos Sur, to the first elected woman in Santa Catalina’s municipal government. My aunt suggested, “You should write a book about our family.”

My father was a writer, and many of my family think I took after him. I started gathering stories and researching the family tree, but life took over. I was a mother of young kids then and had a budding career in laboratory science.

The book came two decades later, in the form of a 57-page pamphlet distributed to the family as a souvenir of our virtual reunion. My nephew helped me edit and collate this work, which we called Memoirs of a Matriarch. Every family member submitted a photo and a story about our grandmother. The slim volume contained her recipes and a playlist of her favorite songs, like Dungdungwenkanto and Manang Biday.

The lull of the pandemic created enough space in my brain to consider expanding the neglected project. “Life is short” ceased to be rhetoric. In 2020, we lost two family members, not from Covid, but the grieving was suspended by social distance.

I asked myself, “What’s the next chapter?”

How about our family immigration story? Over half of our family are immigrants, and each has a tale to tell. I interviewed my relatives about growing up in the Philippines and their journey to America. At first, my relatives were reticent and tentative, but soon, the storytelling gained momentum.

This comment from an aunt sparked my curiosity:

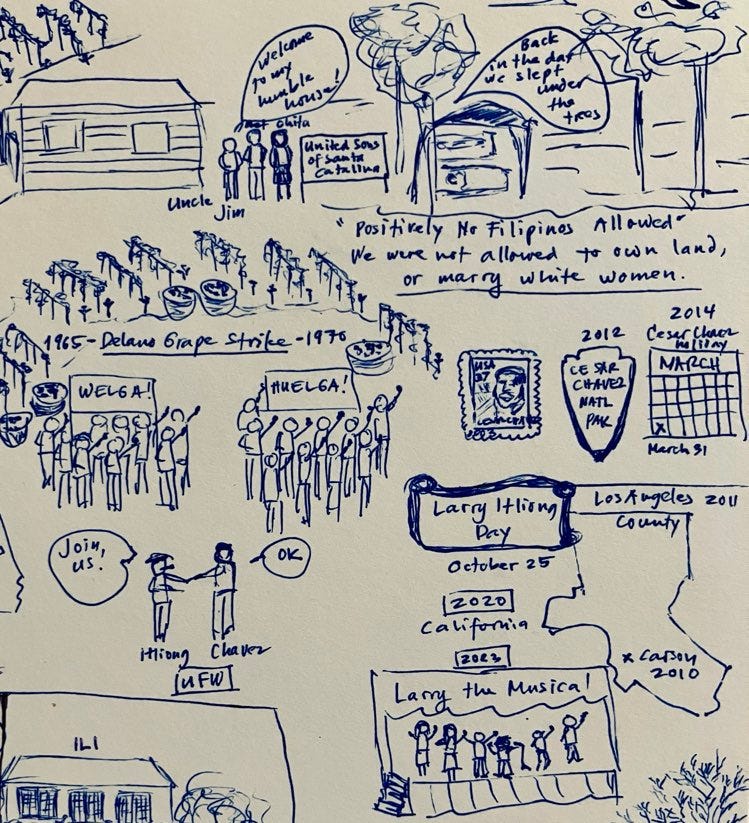

“When we were newly married, we stayed with Uncle Jim. He was proud of his home because he remembered sleeping under the trees back in the day. They were not allowed to own homes.”

A scientist by trade, I ascribe to the motto “Trust but verify.”

So verify I did. I Googled “Filipinos not allowed.”

The first image that popped into my search was a hotel door in Stockton, saying “POSITIVELY NO FILIPINOS ALLOWED.”

I dove into the rabbit hole of research and discovered authors like Carlos Bulosan, an Ilocano migrant worker from San Nicolas, Pangasinan. In America is in the Heart, he chronicled his hopes and disillusionment with the new country. It was a far cry from the land of milk and honey as described by Miss Arnold, his American teacher back home. Here, he was spat on and called a brown monkey. He worked tirelessly in the fields and lived in unsanitary and crowded conditions in the barracks. He ran from white men who wanted to beat him up for stealing their jobs and their women. There were rare moments of joy when he and his buddies scrubbed off the dirt from the fields dressed like Hollywood stars and rode in fancy cars. For a dime, they danced with women in social halls.

Driven by fear and self-preservation, many joined labor unions for protection. Bulosan was puzzled when someone helped him, minutes after he was beaten to a pulp by a mob.

“Why is America so kind and yet so cruel?”

I kept seeing the image of the door and traced its source to an essay called Legally Undesirable Heroes: The Filipino in America published in One Nation in 1945. The editor explained the book’s purpose:

Discrimination is always prevalent in wartime conditions. We decided to make a survey of racial and religious stresses in wartime America.”

Harlan Logan, editor of Look

One Nation, The Riverside Press, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1945

Like Uncle Jim and Carlos Bulosan, many Filipino men started their migrant lives in Stockton. They followed the crop cycles in California, Oregon, and Washington. Some worked in the canneries in Alaska, earning the moniker Alaskeros. One such cannery worker was Larry Itliong, who later became the face of the Filipino labor movement. He convinced Cesar Chavez to join his forces, and together, they launched the Delano Grape Strike from 1965 to 1970, earning contracts and benefits.

The Manongs immigrated to the United States around the 1920s as nationals, the Philippines being an American colony. Their status changed to aliens in 1934 with the Tydings McDuffie Act, which gave independence back to the Philippines. The US offered a one-way ticket back home to the remaining ex-nationals. Uncle Jim chose to stay but was considered ineligible for citizenship and land ownership. The 1920 Alien Land Law was in effect in California until 1956.

They were not allowed to marry white women either. California imposed the Anti-Miscegenation Act barring marriage between whites and non-whites. Filipinos were free to marry their race or Mexican women, creating a generation of Mexipinos.

In a case in 1933, Salvador Roldan sued the County of Los Angeles for the right to marry a white woman but was denied as he was considered a Mongolian. “I am a Filipino, not a Mongolian,” he protested.

The State of California acted quickly and added the “Malay” race to the list of non-whites.

World War II created an alliance between the United States and China. Japan was quick to criticize the US for its treatment of Chinese immigrants. Congress then repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which opened opportunities for other Asians. Uncle Jim naturalized, bought a home, and married a white woman.

The war may be over, but discrimination persisted. I discovered Manila is in the Heart by the late Professor Dawn Bohulano Mabalon. Raised in Stockton, she did not realize the significance of her hometown until she went to the University of California Los Angeles for college. She realized that Carlos Bulosan might even have used her grandfather’s diner as a permanent address, for him to collect mail after returning from his migrant work. Her research led her to a life of activism protesting her hometown's gentrification. Little Manila was wiped out by the freeway construction, with only a remaining portion saved through community activism.

Some Manongs fought for the United States in World War II. The War Brides Act of 1947 allowed them to bring their wives or fiances to the US. Previously, the camp was largely a bachelor society, with a ratio of one woman to about twenty men. With the influx of war brides, communities began to form.

I found another connection to Central California from my cousins who immigrated to Canada. Their grandfather Eustacio worked in Terra Bella. “He sent money back home. That was why my dad was spoiled. He had a father sending American dollars and he did not have to work.”

What a small world. My mom visits Terra Bella every Labor Day Weekend to celebrate her hometown’s fiesta. The San Esteban Circle (SEC) established in 1955 sponsors annual celebrations that continue to this day. In 1988, my mother founded the San Esteban Schools Alumni Association (SESAA). These two groups summon San Estebanians from around the world to the sleepy town past Bakersfield. They celebrate with food, pageants, dances, and mah-jong. Money raised benefits students and community projects in San Esteban, Ilocos Sur.

I wrote about Terra Bella after discovering Patty Enrado’s A Village in the Fields. Her book centered on Fausto Empleo, an old-timer and resident of the Agbayani Village. It was named after Paulo Agbayani, who died of a heart attack on the picket line. The village housed Manongs who had nowhere to go after retiring, or those who were kicked out of the camps during the protests. Click here to read The Halo-Halo Review, a magazine edited by Eileen Tabios:

Return to Terra Bella: A Village in the Fields

I had no clue about the Manongs, although I was only one generation away. I am humbled by the sacrifices our forebears had made.

Recommended Reading:

Return to Terra Bella, inspired by A Village in the Fields by Patty Enrado

Filipino American History Month Festival honors Stockton historian Dr. Dawn Bohulano Mabalon

Filipino American National History Society

How WWII Changed the Anti-Miscegenation Acts

When Hilario Met Sally: The Fight Against Anti-Miscegenation Laws

The Mexipino Experience: Growing Up Mexican and Filipino in San Diego