L is for Lapog, The Town That Never Gave Up

San Juan, Ilocos Sur, #12 of 26 in the ABCs of Recovering Ilocano series

How would you feel if John Philip Sousa’s Stars and Stripes Forever (1896) was banned from being played at Fourth of July celebrations and parades? Next to the Star-Spangled Banner and America the Beautiful, many consider it one of America's most patriotic musical expressions. In 1987, it became the official march of the United States.

It almost seems impossible that the USA, the land of the free and the home of the brave would ever ban a song that sparks the love for one’s country. Or maybe not, if anarchy gets in the way.

Yes, America banned a patriotic song. It happened in my grandmother’s hometown in Ilocos Sur, Philippines, which Mama Ching called Lapog. The song, Aguinaldo’s March by Antonio Escamilla, honored the first Philippine president, Emilio Aguinaldo. Although the leader was not free of controversy, he is considered a national hero for leading the Filipino people in revolts against Spain and America. He declared independence from Spain on June 12, 1898, at the end of the Spanish-American War. The US refused to recognize this move and purchased Spain’s former colony for twenty million dollars in the Treaty of Paris in 1898. It was the beginning of the US as a world power, and it spread its imperialistic reach with the acquisition of Guam and Puerto Rico and the annexation of Hawai’i.

Aguinaldo declared war on the United States and rallied the Filipinos into guerrilla warfare against the American troops. In this iteration of David versus Goliath, the giant won. Aguinaldo retreated north and was eventually captured by the Americans. This little-known war stained America’s burgeoning reputation. The image America wanted to portray was that of benevolent big white brothers who cared so much for the little brown brothers and were there to hold their hands until they could handle their country.

In reclaimed narratives, 1899-1902 was not an insurrection. The Philippine-American War was a conflict between two sovereign nations, and the blood of 200,000 civilians, 20,000 Filipino combatants, and 4,200 Americans was spilled.

Mama Ching may not have recalled the war or listened to Aguinaldo’s March. She was born in 1920, long after the song had been erased from the town’s memory. The Americans burned the town hall in 1903 and forbade the townsfolk from playing the march in the plaza. It dealt a mortal blow to the beleaguered people’s spirits. They were forced to concentrate their population in the town center, a practice called hamletting. The US soldiers monitored farmers, inspecting their carts for hidden guerrillas or provisions.

What my grandmother remembered was caring for her younger brothers, who died from the smallpox epidemic. She spoke of the famines due to the locust infestation and arabas, a beetle that wiped out the harvest. She told me about her gentle mother Oming, who taught her how to operate the Singer sewing machine and weave inabel cotton clothing on the loom. She went to daily mass with her mother, a devout woman who walked the distance despite her limp. Mama Ching grew up listening to government officials debate issues at the municipal council. She learned the art of compromise and diplomacy, skills that served her later in life when she entered politics.

The town dealt with one misfortune after the other, including war and political unrest. It decided to take matters into its own hands by adopting the name San Juan in 1961. This was to invoke Saint John the Baptist’s protection. Since then, it has thrived, boasting many industries such as inabel weaving and buri palm made into hats, fans, and baskets.

San Juan continued to evolve. The feast day of St. John the Baptist is June 24th, but it is during the rainy season. The town selected another date to celebrate. Today, it prospers as a community and is famous for its annual Buri Festival.

Other Philippine towns have also created new identities. After the People Power Revolution in 1986, towns named Imelda were reinvented as San Lorenzo Ruiz (Camarines Norte) and Santa Maria (Romblon). My city changed Imelda Park and restored its original name, Baguio Botanical Garden. A town in Palawan divested its association with the former dictator, replacing Marcos with Rizal, after the national hero. To read my article about Rizal, click here:

I see a pattern in this practice - the new name conveys hope for a better future. This is akin to an Ilocano tradition called Buniag ti Sirok ti Latok. It translates to baptism under a wooden plate. I discovered this tradition when researching our family tree. I was confused as to why one grandaunt was referred to by two names, Feling and Luz. When I asked around, an aunt said, “She was baptized under the latok.”

I was intrigued and mentioned this to my younger brother. To my surprise, he experienced it firsthand when he was about ten. “I was on vacation in Santa Catalina and suffered many bug bites that developed into gaddil (boils). That’s when Uncle Iban and the other Uncles did the buniag and renamed me Quirino.” Elpidio Quirino was a Philippine President (1948-1953) who hailed from the capital city of Vigan, Ilocos Sur.

Buniag ti Sirok ti Latok is a precolonial ritual that was performed when children suffered a near-death illness. Two adults held a wooden plate, and the child was carried or passed under the plate and given a new name. The cleansing ritual ended in a feast. I would think that this must have been done to deter the evil spirits from snatching the child’s soul while it hovered between life and death. In some instances, after colonization, it was also done to reject the Christian names given in church.

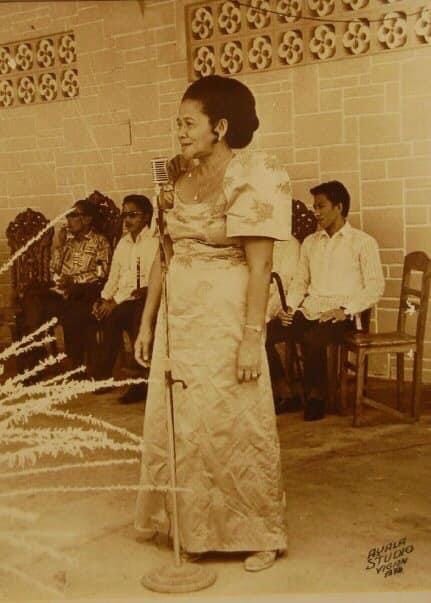

I feel my grandmother’s spirit whenever I read how people and towns reinvent themselves. Mama Ching raised nine kids and outlived two husbands, both town mayors. She managed the family fishponds and went into the tobacco drying business with Governor Carmeling Crisologo. She became a Consejala, the first woman councilor elected into office in Santa Catalina, Ilocos Sur. She rose from a small-town girl with a fifth-grade education to a Vice Mayor in 1972, a post she gave up when she immigrated to the United States. She was only forty-two when my oldest brother was born, and refused to be called Lola. “I’m still young and ‘Lola’ makes me feel old. From now on, call me Mama Ching.”

In this new country, she had crafted a home business cooking pansit, lumpia, relleno, cascaron, and other food for parties. She babysat her grandchildren, teaching my little cousins the same song I learned in childhood.

I have two hands, the left and the right,

Hold them up high, so clean and bright.

Clap them softly, one two, three,

Clean little hands are good to see.

Mama Ching died in 2002 and did not see her son, my Uncle Fr. Albert Rabe, become the parish priest in her hometown. She would have been so proud.

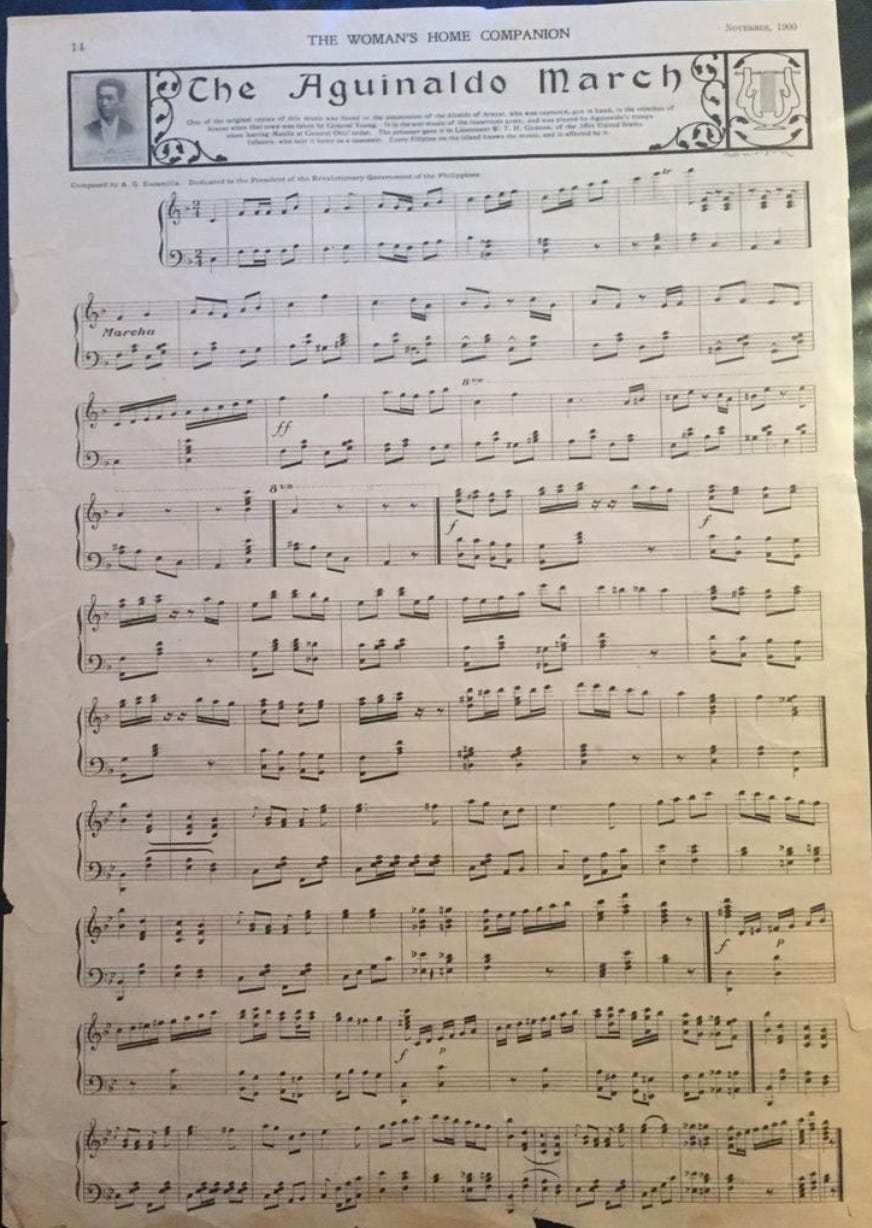

Aguinaldo’s March

Aguinaldo’s March was published in the Woman’s Home Companion in the United States in November 1900, a war trophy from a returning soldier. Its rhythm must have aroused patriotic fervor. Listen to the music:

Antonio Escamilla - Pasodoble "General Aguinaldo" March (1898)

An eBay account describes this piece:

This is an original copy of "THE AGUINALDO MARCH" by Philippine composer A. G. Escamilla as published in the "WOMANS HOME COMPANION" in November, 1900. This is an instrumental piece of music written to honor GENERAL EMILIO AGUINALDO during the struggle for freedom against Spain and prior to the Philippine American War. The interesting description at the top reads- "One of the original copies of this music was found in the possession of the Alcalde of Arayat, who was captured, gun in hand, in the trenches of Arayat when that town was taken by General Young. It is the war music of the Insurrecto army, and was played by Aguinaldo's troops when leaving Manila at General Otis' order. The prisoner gave it to Lieutenant W. T. H. Godson, of the 35th United States Infantry, who sent it home as a souvenir. Every Filipino on the island knows the music and is affected by it."

San Juan and the West Philippine Sea

I grew up hearing “Lapog” and “South China Sea.” Part of the South China Sea is renamed the West Philippine Sea, to demarcate areas where the Philippines has economic control of the waters.

Recommended Reading:

General E. Aguinaldo (Escamilla, Antonio G.) Complete Score

Ilocos Sur Almanac, Municipality of San Juan, Ilocos Sur on page 270

EMILIO F. AGUINALDO (1869-1964)

March 23, 1901: Aguinaldo captured by U.S. troops

Translating Baptism: A Case for Buniag

Portions of the South China Sea is now called the West Philippine Sea

Thanks for posting about this! Interesting memories and research. I wonder if my grandfather and granduncle (both musicians) ever perform the "Aguinaldo March".