Inabel - The Fabric of our Lives

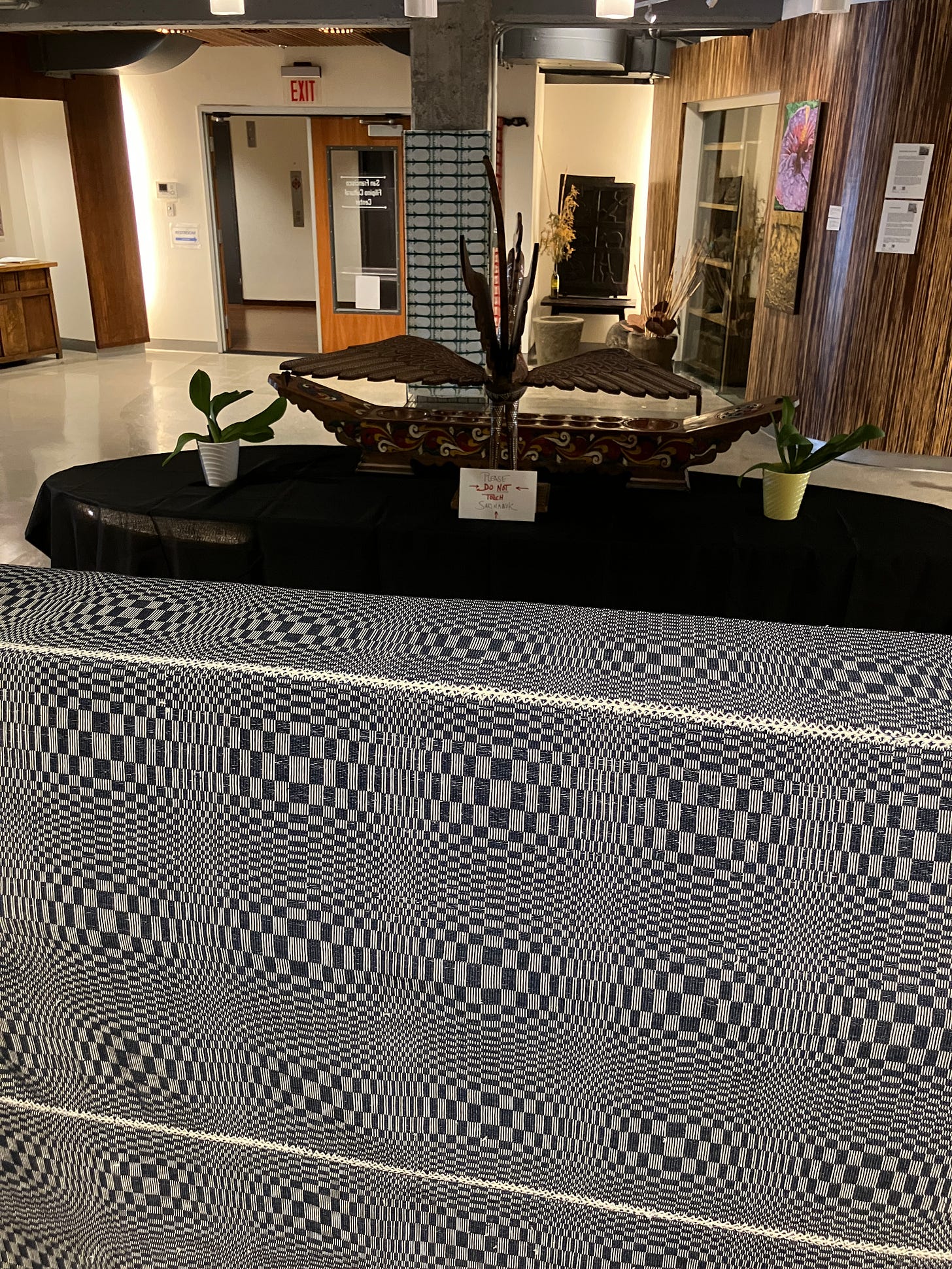

A Visit to the Sentro Filipino in San Francisco - inabel, the biggest sungca, and a taste of Cordillera mural art

On a recent visit to San Francisco, I saw ads on banners and buses everywhere for Ruth Asawa’s display at the SFMOMA. I had limited time, and saved that adventure for another day. I wanted to see inabel at the Sentro Filipino on Mission Street. May is AANHPI month, and I kicked off a celebration of my culture, stringing my high school friends along.

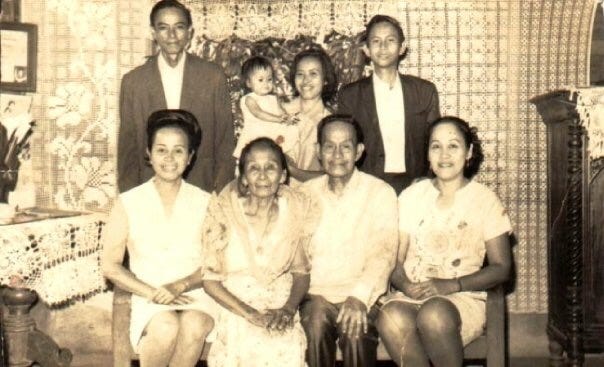

When my paternal grandmother, Mama Ching, was still alive, I asked her what she learned from her mother.

“Sinuruannak nga agdait ken agabel,” she said. I knew “dait” meant to sew. I learned on her Singer sewing machine with the foot treadle. I had to look up “abel” in the Ilocano dictionary. It translates to “weaving” using a traditional foot pedal loom.

My interest in traditional Ilocano weaving sparked many years after Mama Ching died. In 2021, while researching my family history, I remembered the word “abel” and conjured my grandmother as a little girl under her mother’s wing. She would have gathered cotton, spun it into a spool, and dyed it before she wove it using a paddle, all the while coordinating her tiny feet to the rhythm of the loom.

I had seen my great-grandmother Lola Oming only once, on a visit to Lapog when I was four. Much later, my aunts described her as a gentle, devout Catholic who walked with a limp and trod many kilometers to daily mass. I imagined her manner to be like Magdalena Gamayo, an inabel weaver in the video below:

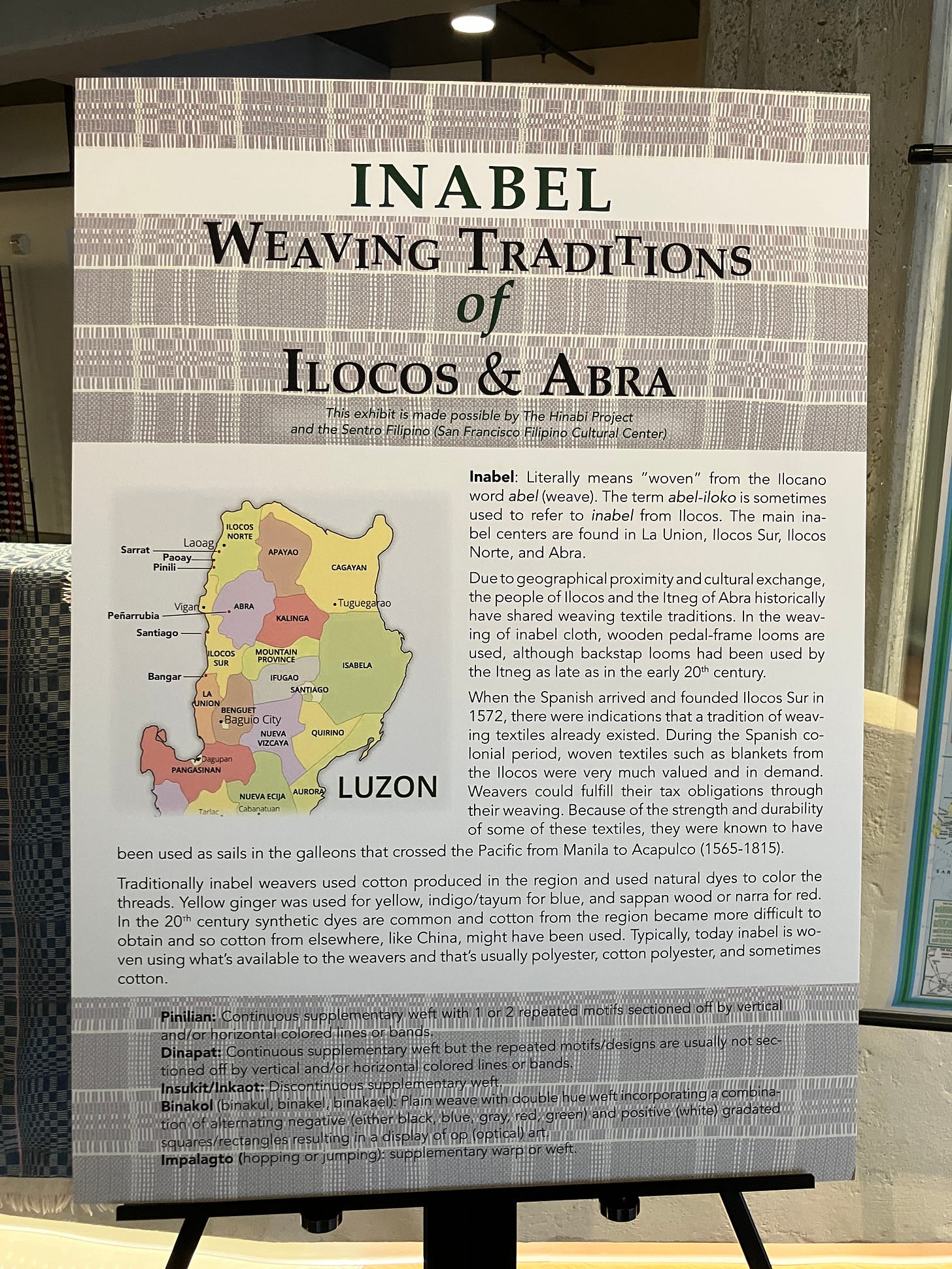

We enjoyed a private tour by Edwin Lozada, co-founder of The Hinabi Project. He explained the different patterns and the areas where inabel thrives. I learned that the indigenous Tinguians from Abra are also called Itneg or Isneg, and the word originated from “iti uneg,” or inland as opposed to the coastal provinces.

Inabel traces its roots before Spanish colonization, as evidenced in an Ilocano epic poem called Biag ni Lam-Ang. These days, inabel is a vibrant industry, but it is challenged with a lack of source material (cotton), labor, competition with mass-produced material, and many other obstacles. This paper, published in the Yale Review on International Studies, has more details: Abel: The Ilocano Weaving Industry Amidst Globalization.

The Sentro also displayed Venazir Martinez’s art. I recognized her work from the murals that people visiting Baguio post on social media. Skinny streets (eskinitas) or dark alleys of my childhood wanderings have become Instagrammable sites.

“Murals really change the energy of a place, and most eskinitas are scary places where bad things might happen. So I wanted to change that one eskinita at a time.”

Venazir Martinez, muralist and street artist

I hope Sentro Filipino will display a collection of our grandmothers’ work. Lola Andang, my maternal grandmother, crocheted elaborate patterns like peacocks and pineapples. She kept them in the narra aparador, where termites surely have eaten them away.

Sentro Filipino reminds me of the Visions Museum of Textile Art in San Diego. I am thankful for passionate people who elevate textiles into an art form. The culture they preserve and celebrate is the story that weaves the fabric of our lives.

Recommended Reading:

Abel Iloco, Museo Ilocos Norte

Abel-Iloko Exhibition, National Museum of the Philippines

The Inabel of Ilocos: Woven Cloth for Everyday

Rachel Lozada: Weaving Together Histories

Very interesting. And beautiful weaving/textiles. Thanks also for the resources your curated.

That’s the fanciest sunca I’ve ever seen! The woven items are gorgeous!